Exhibition of the Maroons in Suriname

On April 6, 2024, an exhibition was opened in the Kennemerland Museum in Beverwijk, Netherlands, about the culture of the Maroons in Suriname. It was an initiative by Mariska de Jong and Iwan Jhintoe, two Maroon descendants living in the Netherlands, and I put a lot of work into it together with Mariska and the museum, thanks to Cees Hazenberg and Teatske de Jong.

|

| part of the exhibition |

Following the opening, I gave a lecture about the Maroons. See abstract below.

About the Maroons and slavery

Surinamese slavery was a system of human exploitation on an industrial scale: in Suriname alone it affected 220,000 people over a period of 200 years. The slave owners were a numerical minority and did not view those people as persons, but merely as a means of production. The victims were often worked to death. The planters used oppression and dehumanization as their tools - humiliation and denial of identity. This still affects their descendants today.

|

| The 18th Century Mariënbosch plantation house |

There would have been no Maroons without slavery. As a result

of the harsh living and working conditions, many fled the plantations into the

forest. They and their descendants are called Maroons.

The connection with Kennemerland

The Kennemerland region behind the dunes to the west of Amsterdam was closely connected with Surinamese slavery, and therefore also with the "maroonage", the flight from the plantations that resulted from slavery.

There was someone named Gerrit Pater, a Beverwijk-born young man who left for Suriname in 1705 and died in 1744 as the richest man in the colony, owning three plantations. Half of Suriname was in his debt.

And many rich country estates around the Wijkermeer - the headwaters of an inlet of the Zuyderzee - were owned by Amsterdam merchants, heartless investors of the 17th and 18th centuries, who had interests in plantations.

|

| The Akerendam mansion at Beverwijk was the property of Amsterdam plantation owners |

The first Maroons

The first Maroons probably already fled the plantations in British times. After the conquest of Suriname by the Dutch in 1667, the British planters gradually departed. 15 years later, most plantations were Dutch property. The number of plantations then grew rapidly, increasing the number of enslaved workers and the flight from the plantations.

Resistance and peace

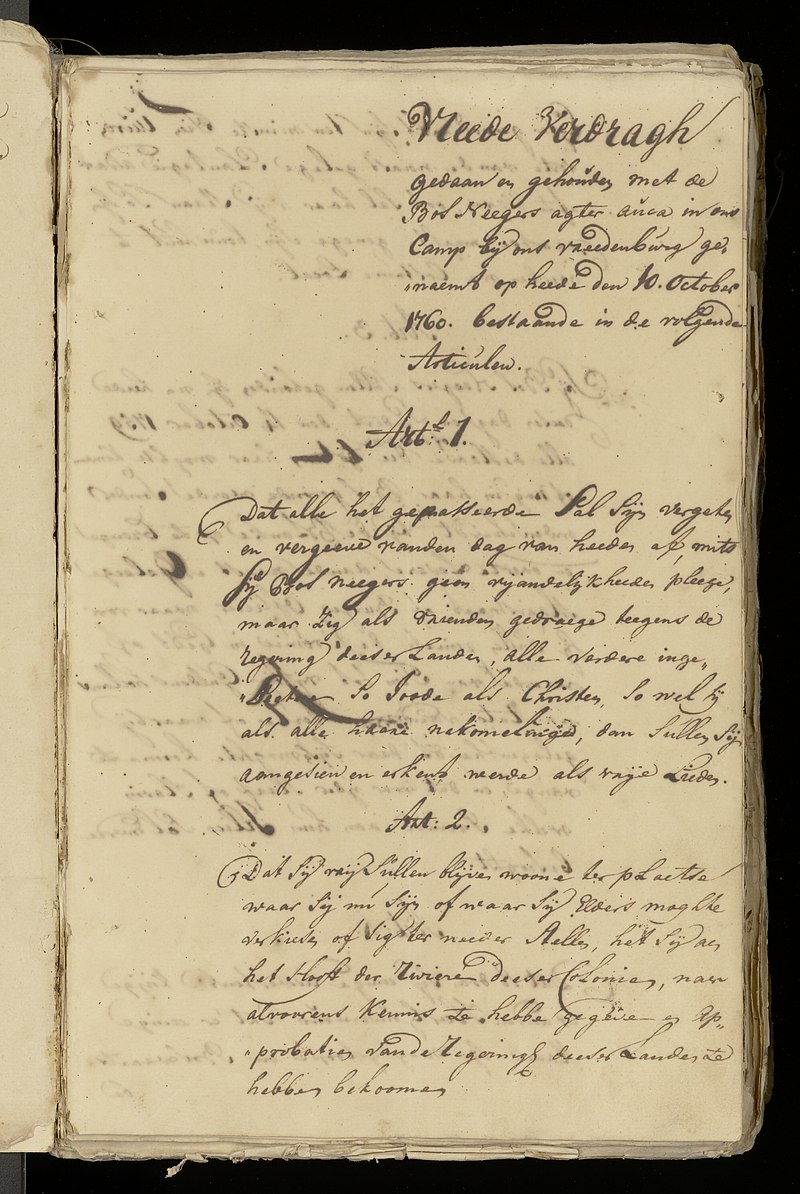

By 1750, about 3000 Maroons lived deep in the wilderness of Suriname. Many were engaged in a bitter guerrilla with the planters and the government, who were steadily losing the struggle. In 1758, Paramaribo finally throws in the towel and offers peace to one Maroon tribe: the Okanisi. Then in 1760 the first treaty follows with Okanisi, followed by treaties with the Saamaka and the Matawai. Other groups however never make peace, such as the Aluku of Captain Boni.

|

| The 1760 peace treaty between the Colonial authorities and the Okanisi tribe. source: National Archives, through Wikipedia. |

The Surinamese Maroons of today

Present-day Maroons are directly descended from the Maroons of

the past. The peace treaties allowed a hard but secluded and peaceful life in

the forest, and as a result, they preserved many of their original African

traditions.

|

| Maroon village of Gunsi, upper Suriname river. |

African roots

In Africa, traditionally there is an animist belief and a strong bond with the ancestors. This is clearly present in today’s Maroons. Many of them feel a strong connection with nature, everything around them containing its own power or spirit. They practice the water ritual, which honours their ancestors, and many other rituals, for example around life and death. They have also preserved the oral storytelling tradition of Africa such as the stories about Anansi, the spider.

The bond with nature

An example of the bond with nature is the Kankantri, the African kapok tree, which also grows in South America. The Kankantri is worshipped in the forest because it houses a busigado, a forest spirit. Sometimes a meal is placed under the tree for the busigado, and unaccountably, the food has always disappeared the next morning!

|

| Kankantri, the ghost tree |

Rituals and ancestors

Rituals are highly important in the Maroon culture. They strengthen the ties within the community and with the ancestors, at birth, marriage, illness and death, but also on other formal occasions, such as the opening of the exhibition in Beverwijk. Here the water ritual was carried out, which has the deeper meaning of the journey of the ancestors over the ocean and also has a cleansing function. In addition, a libation was offered to Mother Earth. I was present at the ritual, and it made a great impression.

|

| Anansi - photo and overlay by Ted Polet |

African storytelling

Where there is no written language, knowledge and wisdom are transferred orally from generation to generation with stories, often about Anansi, the spider, which were handed down from West Africa. Those stories aren’t just for fun - they also have a deeper meaning. In Africa, Anansi, the son of Mother Earth, is the messenger of the gods to mankind. He steals wisdom, but accidentally drops it to the ground. And then this happens ...

The river took the wisdom that Anansi had gathered to the sea, which it spread all over the world.

And that is why a little bit of wisdom lives in us all.

Mother Earth

In Ghana, Mother Earth, the mother of Anansi, is called Asaase. In Suriname she is called Mama Aisa or Gronmama (literally: Earth Mother). She is the goddess of the dry, exhausted earth and of death and welcomes the deceased in the spirit world. You even have to ask her permission to bury someone’s body.

|

| Asaase Yaa/Mama Aisa (source unknown) |

But she is also the goddess of fertile earth and new life - look at the infant in her arms in the image above. And so once more, we touch the beliefs of the Maroons: a life cycle that starts before birth and continues after death.

Secret messages

The Maroon culture is full of secret messages, which are well

understood by the recipient. They are in embroidery patterns, wood carvings and

the painted pattern on utensils. The 'pari' or paddle is used to steer the pirogue, but it also directs life, which is shown in the carving at the top and the painted pattern on the blade.

|

| Pari, or paddle for a pirogue. Photo by Mariska de Jong |

The secret messages are also in the language of the Apinti drum and of the "telephone tree" .

Apinti

Apinti is a way of speaking with a drum. Its origin lies in West Africa, and the sound can be heard for miles in the jungle. Once it was used to signal the presence of an enemy in the forest. Speaking with the drum is a difficult art. The drummers must be inaugurated and must have a thorough knowledge of the rules. Apinti also has a ritual meaning. The drummer not only speaks to people, but also with the supernatural.

|

| Apinti 'doon' - the drum played in the forest. Photo by Mariska de Jong. |

The telephone tree has deep recesses in its trunk, and gives a hollow booming sound when you knock on it it with a stick. The language of the telephone tree is the same as that of the drum.

|

| My friend Olan Dinge knocking on the trunk of the telephone tree, Gunsi, upper Suriname river. |

|

| The flyer designed for the exhibition |

No comments:

Post a Comment